There is one book you need to read if you work in risk regulation: Cass Sunstein’s ‘Risk and Reason‘.

If you don’t have a copy, or have it, but have not digested and noted every page, you are like a preacher who does not own a copy of the Bible, let alone read the good book. But, you still stand up in the pulpit at the Sunday Service to preach the gospel

I know most people don’t like to core texts. They prefer a wiki summary. Take the time to deep dive into this classic. The wealth of knowledge you’ll get from it is worth the time.

Sunstein visit to Brussels

It would be good to have Sunstein’s rational thinking in Brussels. He calls for an approach when government action is focused on the major risks, rather than trivial risks, that threaten the public health. Those risks are well known: poor diet, obesity, indoor air pollution and sun exposure. Government action, in Europe or the USA, does not focus on them.

Like Vaclav Smil, even if he Sunstein visited, I realise that many inside the Commission’s political leadership, would not know who he is, and be unreceptive to his thinking. The experts in the Services would flock.

Sunstein is best known for mainstreaming the idea of cost-benefit analysis. That’s the idea of looking at the costs and the benefits of regulatory action. It looks at it in term of monetary value, often a statistical value of life. It also looks at costs and benefits of alternatives course of actions. Sadly, this idea is still not mainstream in all Commission departments, even if it is in the Better Regulation Handbook.

I worked with the idea of the cost-benefit analysis in the first daughter-directive on ambient air (1999/30/EC). It was clear to most that the benefits of taking greater action to control air pollution emissions outweighed the costs. I’ve always found cost-benefit analysis is the greatest benefit for getting good environmental legislation adopted and passed.

What are the real public health risks in Europe?

If Europe did a serious evaluation of the lives saved by selected regulations, my hunch is that would find out the resources are badly misallocated. Governments tend to respond to well-organised campaigns by savvy policy entrepreneurs and public concern, often ignoring the real health risks.

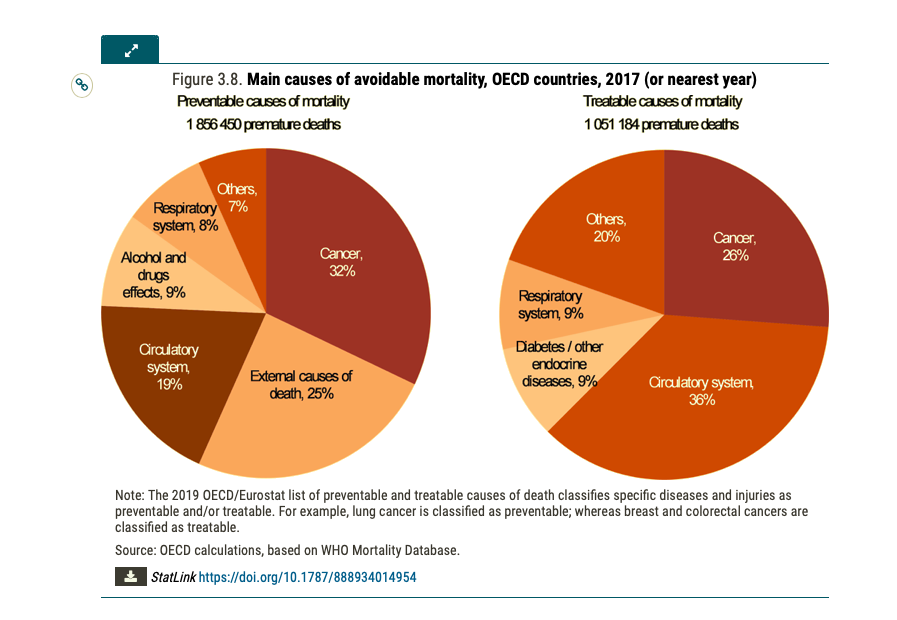

If you want to get a better idea about what the preventable deaths in Europe are, prepared pre-COVID-19, have a look at the OECD-EU’s joint work.

Source: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/3b4fdbf2-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/3b4fdbf2-en

External causes of death are from traffic accidents, suicides, and murder.

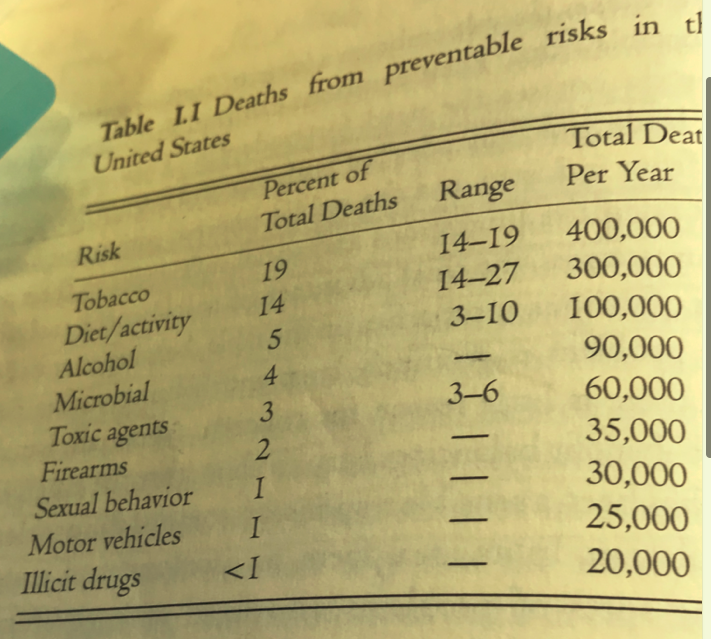

In the USA things are similar, except for the impact of drug deaths.

A flawed European regulatory approach to risk regulation

Instead, regulators and politicians across Europe, prefer an approach that:

1. premium on the need for immediate, large scale responses to long neglected problems

2. command and control regulatory controls

3. focus on the existence of problems rather than their magnitude, and little to any interest in priority setting

4. indifferent to the costs of achieving regulatory goals

5. distributional goals – worker or environmental safety at the expenses of corporate profits

6. moral indignation at those who pollute and other risks

That this approach has a poor track record of enforcement, implementation, or delivering the expected results, seems to be forgotten.

An alternative approach to deal with the serious risks

Sunstein calls for an alternative approach for taking action. My own view is that, if adopted, it woudl accelerate action where it is needed, and bring about major public health gains. This includes:

1. Assess the magnitude of the problem. Look at the numbers and the size of the problem.

2. Take into account tradeoffs. What are the consequences of trying to reduce the risk? What are the 2nd and 3rd order consequences? What are the health-health trade-offs?

3. What are the best regulatory tools to deliver the goals and minimise the costs

How real people think about toxicology

I spend a lot of time lobbying about chemical substances. Sunstein explains why most industry lobbying on chemical substances is bound to fail. He shows how industry, in particular industry toxicologists, are totally out of sync with how most people think about substances.

As Sunstein puts it, the public see things like this:

1. There is no safe level of exposure to a cancer-causing agent

2. If you are exposed to a carcinogen, then you are likely to get cancer

3. If a scientific study produce evidence that a chemical causes cancer in animals, then we can be reasonably sure that the chemical will cause cancer in humans

4. The land, air, and water around us are in general, more contaminated now than ever before.

5. Natural chemicals, as a rule, are not as harmful as man-made chemicals.

6. All prescription drugs must be risk-free.

The public overwhelmingly agree with these statements; toxicologists do not. In my experience, most politicians and officials side with the public.

If industry ignores this reality for most people, officials and politicians, what they say is likely to increase concerns about the risks, and win more people over to back tighter controls.

Why does this make sense to people

This thinking is logical for most people. The reasons are:

1. Many people think that risk is an ‘all or nothing’ matter. It is either safe or dangerous. There is no middle ground.

2. People trust in the ‘goodness of nature’. Man-made is more likely to be dangerous, than products coming from natural processes.

3. Many people back zero risk in some activities. They want to abolish risk in some areas.

Experts don’t agree with these ideas. Industry lobbyists don’t. Toxicologists employed by the industry are far more optimistic about chemical risks than toxicologists employed by governments or academia.

The gap between toxicologists world view and the public is huge. The challenge is that politicians and officials listen more to the public than to toxicologists.

Dread – A Rational Response

Unsurprisingly, some risks are “dreaded” and other risks are not. People dread getting cancer. This makes sense, the risks for getting it are not low.

If you are really serious about reducing risk

If European governments invested to reduce the risks from smoking, poor diet, and alcohol abuse, they would deliver ‘extraordinary’ health gains. Instead, most government work is on ‘infinitesimal’ risks.

Action against real risks can easily be ignored unless championed by savvy policy entrepreneurs, or courageous technocrats and politicians.