There is a lot of public policy writing in Brussels.

A lot of this writing is designed to influence and persuade officials and politicians. You are writing because you want the reader to take action in your favour. As most decisions in Brussels are taken by ‘written procedure’, good writing will help you advance your case.

Good policy writing helps advance your client’s interests, poor policy writing is hard to understand, and harms your client’s interests.

4 Criteria to Judge Your Writing

There are 4 criteria by which you can test your writing. Is it:

1. Accurate

2. Clear

3. Persuasive

4. Retainable

Accurate

If it’s inaccurate, it’s worthless. It should not cite selectively or mispresent as this is deceptive. Accuracy is vital.

Accuracy must always be judged in terms of the space available. A longer piece can be more accurate than a short one, but if it is so long that no one in the targeted audience reads it, it’s worthless.

Accuracy requires you to address points that may not be in your favour that the reader will have questions about. If you don’t, it is useless, it’s worthless.

Clear

If it isn’t clear, not many people will be able to put it to good use. If so, it is useless, it’s worthless.

Your reader is likely reading it late in the day. They are tried. They want to get home to their friends or family. If it is not crystal clear at 7 p.m. on a Friday evening, it does not work.

Try font 12. Most readers over 50 will find it hard to read anything smaller. Random bolding of text distracts the reader. Clear and precise writing stands on its own.

Persuasive

If it is not persuasive, no one will put it to good use. If it is, it is useless, it’s worthless.

Your reader needs to take action after reading it. The need to decide to back your position by intervening in a procedure or voting for you.

If after reading your briefing, the recipient lands up confused, irritated or less likely to support your case, your writing does not work.

Retainable

If no one can recall its main points a week later, no one will put it to good use. If it’s useless, it’s worthless.

A good way to see if your material works, is to give it to a colleague who does not know the issue. Have your colleague explain it to you. If your colleague did not get it right, re-write it.

Get it right. Make it clear. Make it persuasive. Hope they remember it.

How To Apply This

These criteria may set a threshold that you may think hard, maybe impossible, to meet. Bad writing is a lot easier to produce than good. 44 pages is a lot easier to churn out than 1 to 2 pages.

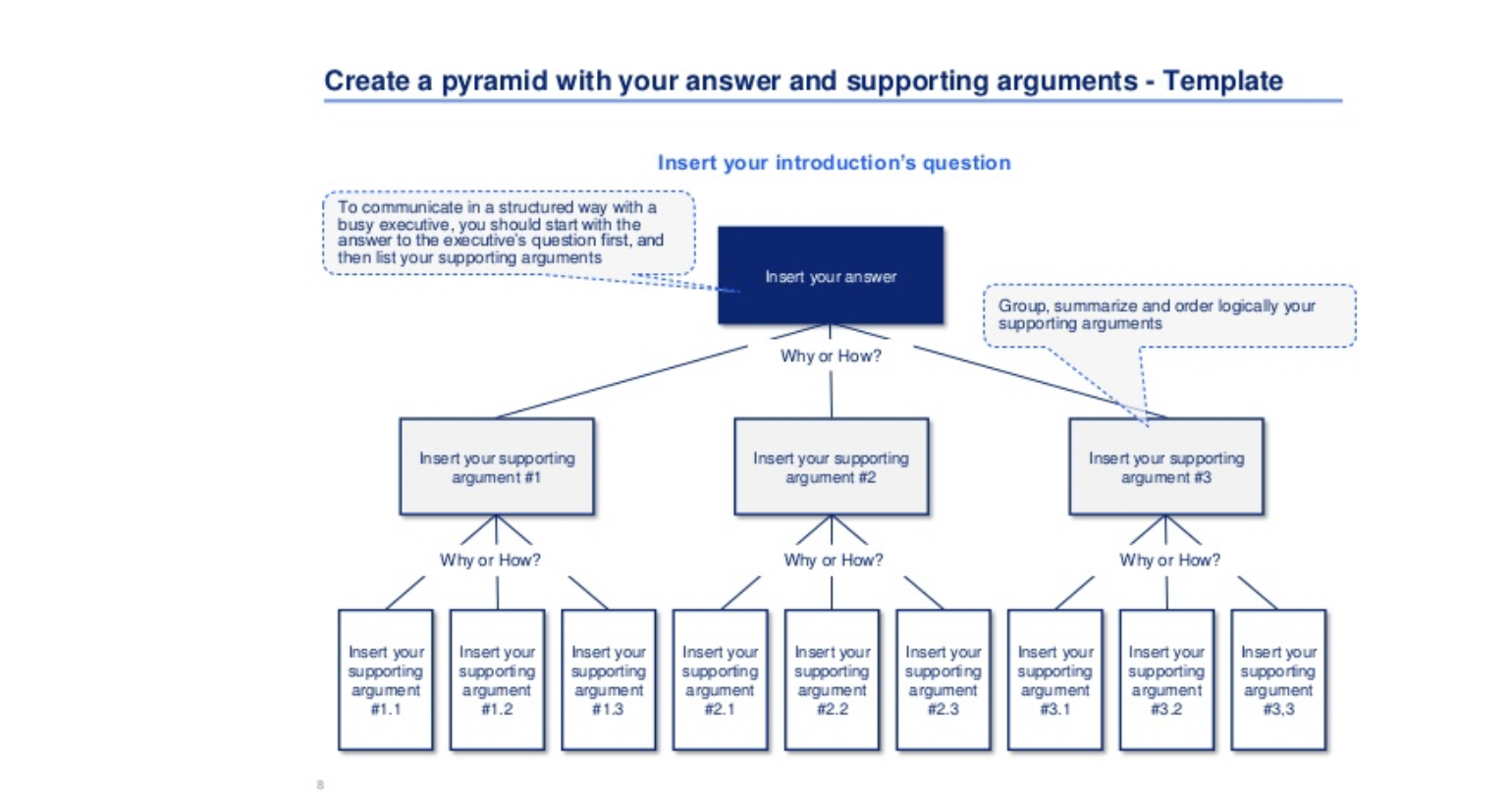

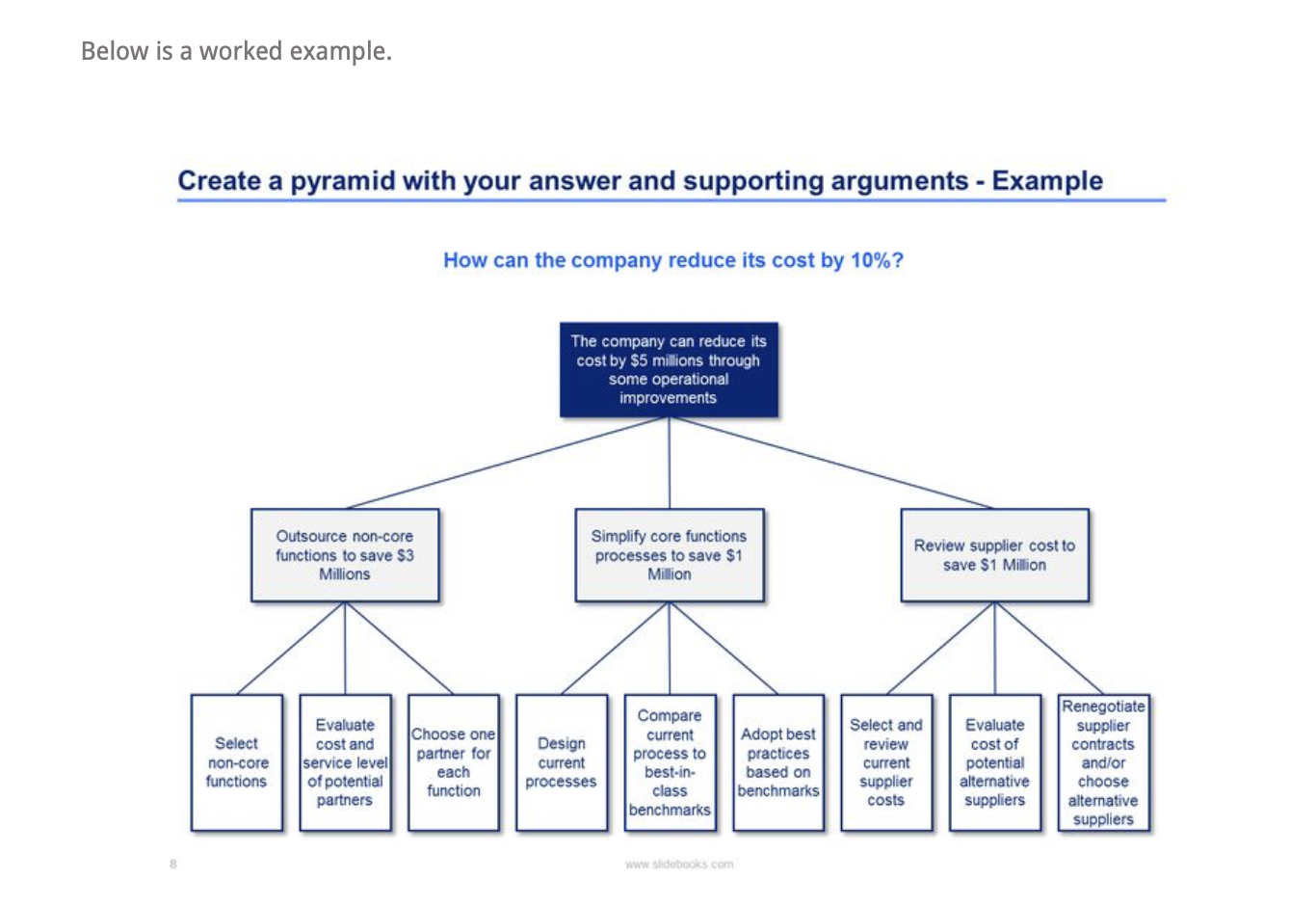

There is an effective system for producing good copy – Barbara Minto’s ‘The Pyramid Principle: Logic in Writing and Thinking.

If you apply her model, you’ll stop producing papers that are hard to understand, overpacked with “issues”, and that lack any clear logic.

My Summary

My own take away from Minto’s advice comes down to:

1. When you write, put yourself in the reader’s position. Does your writing answer the question(s) that he/she expects your document to answer?

2. You should provide the answer at the start. Provide the answer to the question that is in the reader’s mind. This is a very different question than is in your mind. You are writing to persuade the reader.

3. Keep the tone fair and objective. Your writing should not be a means to get your/organisation’s/client’s inner angst into words. Too much policy writing is psychologically depressing and hard to understand.

4. A paper – a position paper, briefing, or memo – should deal with only one central issue. If there is more than one main idea, put that down into a separate paper.

4. You should provide the answer at the start. Provide the answer to the question that is in the reader’s mind.

5. The language should be so that your grandmother would understand it. Use words that your reader will understand. Use plain English and not Sanskrit.

6. The ideas in the document should relate to each other. Every section (and the supporting paragraphs) should all support the one central idea that you have given at the start.

7. The sections should relate. Every section should convey a main idea that supports the Answer you gave at the start.

8. You need to avoid ‘new’ ideas jumping out that has no logic to the section or to the paragraph.

9. Every paragraph needs to convey one supporting idea. That means you have around 7-9 supporting ideas to put down in your paper – not 79. 5 is even better.

8. You can chunk down a paragraph into:

-

A statement of the issue

-

A summary of the public policy problem

-

A proposed solution, and

-

Supporting evidence

Example

Here is a good template and example:

I use a template Mindmap.

Producing positions that are accurate, clear, persuasive, and retainable is not easy. It is a lot easier to produce writing that no reasonable reader can understand. But, the benefits of having your ideas co-opted by officials and politicians make the hard work worthwhile.