There are 3 main ways you can communicate:

- Writing

- Listening

- Speaking

Personally, I will come out and admit I am one of the few people in Brussels who does not believe in telepathy. I don’t believe that ideas permeate the ether from unknown animal spirits. Of course, I remain open-minded on this.

- Writing

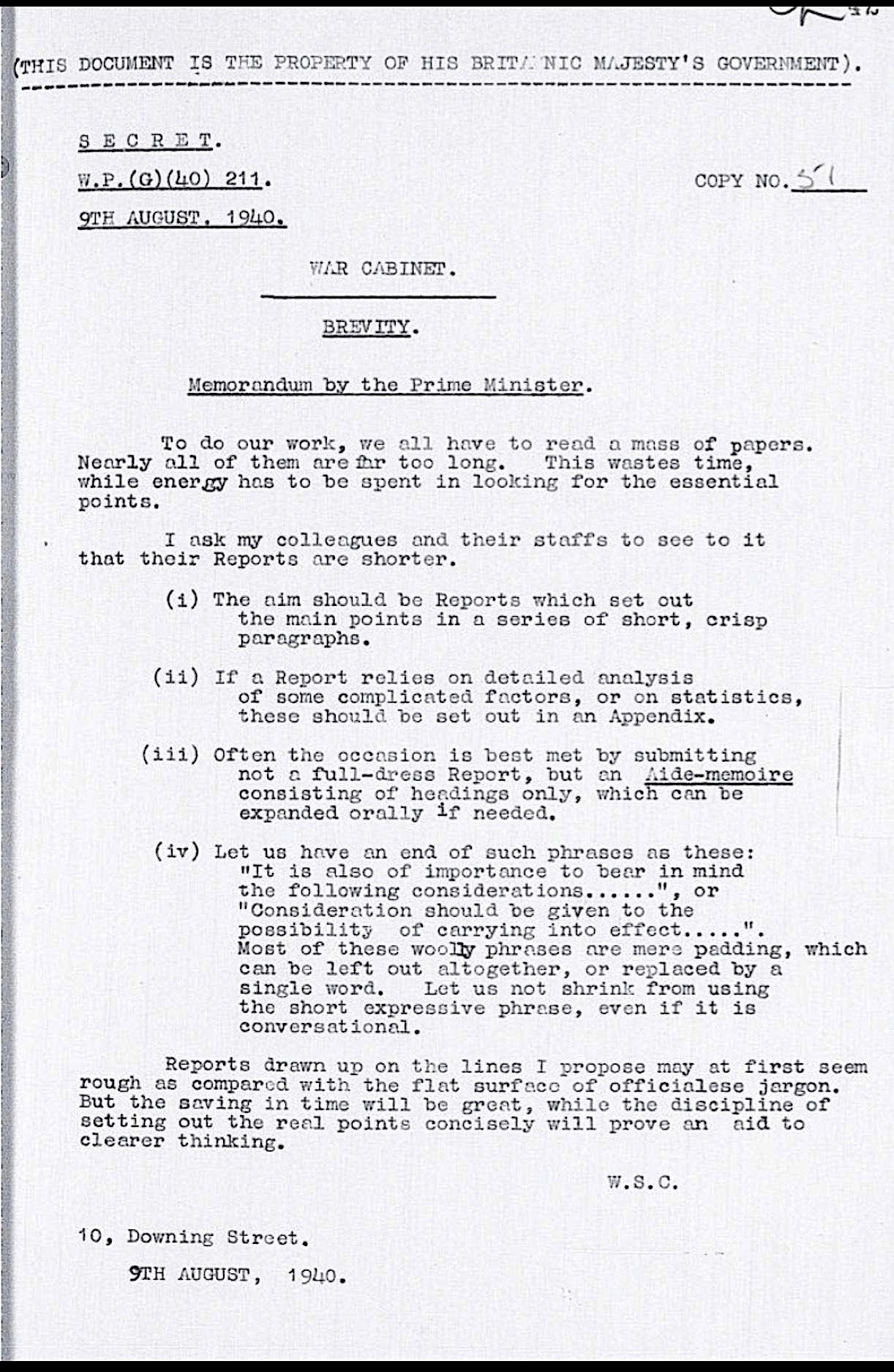

Winston Churchill took the time out to write this note to the British civil service on 9th August 1940.

It is well worth reading. I have taken to sending it around. Let’s take a moment to remind ourselves what this means. During the Battle of Britain and Britain faced the threat of invasion, the British Prime minister writes a note to ask for clear notes from officials. He thought clear communication was vital.

I think the case made for plain English is as strong today as it ever was.

Too much writing by lobbyists is poor writing. There is no need for it. It detracts from the elemental obligation to communicate.

- Two simple tests

There are two simple tests to judge your writing.

7 pm on a Friday

First, can it be read once on a Friday evening be read by an official, understood in one reading, and a response prepared immediately? If your writing does not pass the ‘7 PM’ test it needs more work on.

CEO

CEOs face a packed agenda. They are asked to make important decisions, many vital to the future of their company.

They also spend a lot of time reading advice and recommendations. Whilst they may not spend as much time as Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger, who read several hours a day, they need to be able to digest complex and varied issues.

All too often, public policy and political writing is polluted with jargon. Some areas, like chemicals, fisheries and energy have readers been drowned in acronyms. Poor writing does not inform good decisions.

- A Briefing in 9 points

I think the most complex issues can be got down to around 400 words.

This means one page of A4 at font 12. I despise font 11. After the age of 40 I find it hard to read. I like 3 sections:

- What is the Issue/Problem

- What is the recommended solution

- Any relevant background

That is around 9 paragraphs, divided by headings.

I’ll be the first to admit that plain English is not easy. Clear concise, plain English is hard work for the writer. It is far easier to say something in 300 words than in 30. Yet, it is not a reason to be lazy to dull the senses of the reader.

Complex writing is often a clear sign that the writer’s thinking is at best fuzzy and their case weak. Needless padding is often a sure sign of a weak case, and needs to be treated with great caution.

- Guides

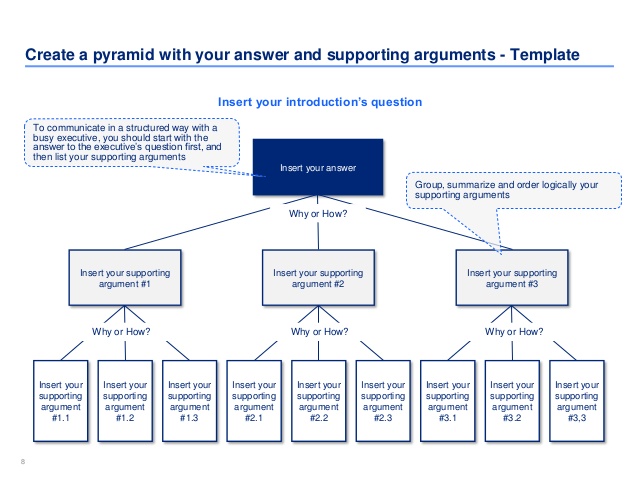

Barbara Minto’s Pyramid Principle provides an excellent system to help you write well. Minto trained a generation of McKinsey consultants to communicate clearly to CEOs. Re-training yourself to use this system is not easy, yet the effort is worth it. I have seen people adopt the system. Their thinking comes across so clearly that their written recommendations are adopted without question. Rudolf Flesch’s books are superb.

- Don’t land up in the in the waste paper bin

You’ll send a lot of letters and position papers to civil servants and politicians. It is useful if they are read and acted on positively. Many are not.

When I worked for a British Labour MEPs in 1997 I discovered that very few Social Democrat political advisers ever read any of the many letters from UNICE. I found this curious why most progressive MEPs put the leading business association’s letters straight in the bin. The answer was simple. They too often read like a neo-Conservative call to arms, were too long, and poorly written. Personally, I thought this was a shame. I discovered some useful suggestions in the last paragraphs on page 2.

- When to share your information

If you have a meeting with a politician or official, I think you’ll get a lot more out of the meeting if you send them a briefing note in advance. Ideally, this would go to them a week in advance and no later than 48 hours before. If you want to get a change in a position you need to do this. Otherwise, you are likely just wasting their and your time. Bringing it along on the day is plain silly.

- Be constructive

I am of a certain age that being constructive and civil is a given. I am in a minority. Hectoring letters don’t work. Letters that bend the facts are petty and counterproductive.

When of my first tasks when taking up a file in the Commission was to respond to a complaint from a group. The complaint amounted to the Commission never listening to or meeting a group to discuss an important file. It was serious enough that the Commissioner wanted a reply the same day.

After I spent a few hours going through the paper files I was able to prepare a reply. I prepared a long annex that detailed each of the 50 odd meetings with the group and 200 letters that had been exchanged. I felt comfortable to note that whilst the Commission may not have agreed with them on all points, it was not accurate to claim the Commission had never met them or dealt with them. This sort of practice is still too common. But, the hazard for those who continue it, is that they will not be trusted. And, when trust is lost, you’ll be ignored.

Equally, if you disagree with a position, you should let say so. You should not hold back. The need for your writing to be persuasive and supported by evidence, often detailed in a supporting annex, is more important than ever.

- Everything is public

I think you should write every note, letter and position as if it is a public document. Freedom of Information and leaks will more or less guarantee it finds its way into the public. Here, poor writing will draw out wrong inferences and help paint you in the worse light possible.

- Are you communicating and persuading?

Too many organisations, private sector and NGOs, want to denude the forests of Finland and use more and more paper. I have found this faith in reeling off position papers and letters to the Commissioner at best strange, and too often pointless.

- Avoid Jargon

I dislike jargon. At best, it can only be used in the very small cliques who use it as shorthand. I got off jargon when I was at WWF. I am not a fisheries biologist and had no real idea what MSY meant and the equations that scientists used to make quota recommendations.

I stopped the use of equations in letters to the Fisheries Commissioner. As soon as he got his annual letter, the Head of Cabinet invited me around to meet. He knew someone new had joined. It was one of the first letters he and the Commissioner understood. Only a few people in the department knew what the equations meant.

Further Reading

Barbara Minto, ‘The Pyramid Principe: Logic in Writing and Thinking’

Anything by Rudolf Flesch