I thought it was time that I write out the model I use for winning legislative political campaigns in the EU. I have been asked to write it before, but I now have a lot of time on my hands, so got around to it.

I am sure there are many holes in it. I’d welcome hearing from you.

The ideas behind it are not complex. They are born from nearly 20 years working in Brussels working on passing or campaigning to influence EU legislation. During that time, I have looked to refine the model, take on board what works, and more importantly, discard what does not work. As a model, it is tested with each new campaign, and the model is constantly refined. If it does not work, I’ll get rid of it.

I could summarise the approach as “speaking to the right people, at the right time, in language they understand”. I’ll go into more detail in four sections:

- What game are you playing

- Value Based Communications

- The key people

- Understand the game you are playing

What game are you playing

I am always curious if people campaigning or lobbying on a proposed law are in the business of winning or whether they want to convert people. There is a big difference.

If you want to win, at the end of the day, you want your proposal (or amendment to it) to be adopted. You don’t really care whether the majority of politicians voting for your proposal (or officials if it is delegated legislation) support your position, let alone believe in it. All you care is that for that one moment in time when they come to vote on it the majority you need back your position.

I have seen politicians and officials back an option I have campaigned for knowing full well that many of them opposed it personally. But, events were engineered so that at the right time, on the right day, they voted for the right thing.

On the other hand, I have seen many lobbyists, campaigners, companies and NGOs wanting to convert people to their position. I find the practice of converting people to be time and resource consuming. Given so many NGOs and companies are in the business of converting non-believers and opponents to their position I am sure it must sometimes work. I just guess that my not seen visible signs of mass conversions of non-believers and opponents is a sign of being general sceptical and broadly agnostic.

But, the general practice of “conversion or nothing” dominates Brussels, and I think most political campaigns. It perhaps explains why so few campaigns deliver. It’s like Jehovah Witnesses going to the Holy See and being surprised how few, if any, of the flock of Rome, admit the errors of their ways and switch sides. In reality, many companies and NGOs are asking non-believers and opponents to accept that they are wrong, usually on an issue that is deeply important to them as an individual, and publically convert. That the issue is usually sold to them in terms that amounts to as nothing more sophisticated as ” you can’t do that because it will hurt my profits”, or “we need to stop modern industrial production, even if the technology does not exist to replace it” – here I basically paraphrase opening gambits I have heard from industry and NGOs – it is not hard to understand why the modern business of conversion is a hard slog.

Value Based Communications

I have written about Value Based Communications before (please see here).

If it worked for Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair it can work for you. It works for Greenpeace and Toyota. Yet despite working, a lot of people don’t like it for what I can see as two reasons.

First, they think communicating to people in ways that makes sense to the target audience as manipulative. Second, a lot of people don’t like idea of changing the story they tell to different groups of people.

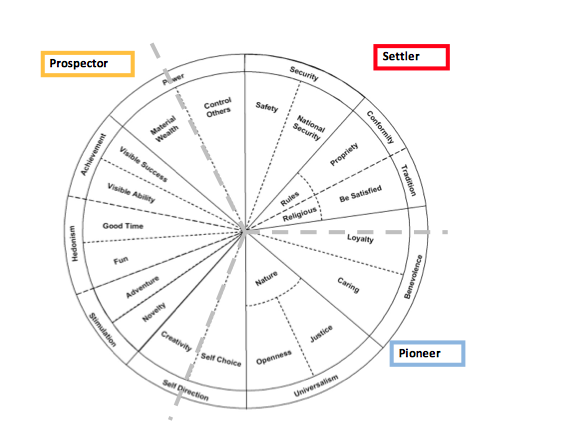

First, the business of political persuasion could be seen as manipulation. It is about putting the best set of ideas forward to a given individual that will persuade them. As people seem to have one of three value sets (Settlers, Prospectors, and Pioneers) who look at the world in very different ways, the only hard part is to re-articulate your case in language that resonates with each of those three groups. It perhaps explains why many people use the same arguments to Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, Liberals, Conservatives, Greens, Communists, nationalists and fascsicts. That this assortment of political interests look at things very differently shows that it is vital to adapt your story for these political traditions.

Second, only very unsuccessful salespeople use the same story line all the time. Why people buy into something is individual. Not understanding what makes those people tick you are trying to sell to, and adapt your case and language to support that case, is at best lazy and at worst politically suicidal.

I find the chart below helpful in that it provides examples of what drives people in Settlers, Prospector, Pioneer groups. The language and case you need to put to these groups is very different to win them over is very different. You can of course use your standard presentation with the same language to everyone, but please don’t be surprised if it does not influence many people.

I have used this on some campaigns. The most dangerous side effect I found that a very broad coalition of politicians supported the issue, for a whole variety of reasons, and most of the time not for the same reasons that the client backed the campaign.

I recommend anyone to read Chris Rose’s book “What Makes People Tick” and the excellent analysis from Pat Dade at Cultural Dynamics.

Key People

I used to think that on any given issue on a piece of EU legislation 500 people count. I have just looked over a very detailed list of the key decision makers across the EU 28 on an issue I have followed closely for a long time. To my surprise the number is 228 people.

That list includes:

- Commissioners

- Cabinet Advisers

- Key officials in the Services, including drafters, legislative team, inter-service steering group

- MEPs working on the issue

- Key advisers to those MEPs

- Ministers

- Key political advisers

- Permanent Representative officials

- Key Directors and officials in national Ministries

- Active and influential journalists in the EU 28

Each and every one of those people has a name, email, phone number, mobile number, and postal address. Each and everyone of them has a general position on the broad issues, and sometimes specific positions on specific issues. For key people, specific argumentation points will of course be developed in advance, and even have rehearsed. Understanding from where they are coming from and adapting your conversation to win them over is essential.

Whilst having the list in advance, please bear in mind that the list will alter for two main reasons. First, some key players will appear during the process, that were at the start of the process unknown. You can even sometimes engineer for new players to enter the process if you think that will assist you. Sometimes a President may overrule a Minister after some well targeted media. Second, governments in an EU of 28 are having elections, and Ministers come and go. Key allies or opponents one day may not be in power the next day. The list is of course a living list.

Also, depending where a proposal is in the process will be vital. At the start of a proposal, the Inter-Service Group and Cabinet leads will be vital, but the same people will have little or no role when the final conciliation meeting starts.

Understand the game you are playing

Europe deals with two main types of legislation: ordinary legislation (co-decision) and delegated legislation.

The process for the adoption and passage of both types of legislation are very different. The people who make decisions and by why what majorities are very different. All too often campaigns use a reverse read across and hope what worked once before will work again. This in my view takes faith healing to a new level of blind adherence. If you’d don’t read the correct map (the process and the rules for your specific proposal) it is very likely that you will get lost and not turn up on time, if it all.

All too often, campaigns will blame the system as being unfair when they get lost and loose. In reality, what has happened is that the campaign has not looked at the right map, or not even picked up a map at all. In retrospect, their loss is not a surprise, it is more just a foregone conclusion.

Finally, the opportunities for planting seeds that lead, over time, to new proposals and maybe laws are plentiful. Yet again, few people take the time to plant the seeds. For one NGO I worked, a report we published that provided a template solution to a seemingly intractable problem, which provided substantive, practical and real life solutions, was co-opted in large part by the Commission and tabled in a proposal. This long-term thinking requires you to delay the instant gratification of instant changes, and rather allow ideas to blossom over years and have them become mainstream and co-opted by others. The results are usually more positive and longer lasting. It’s better to help at the very start design a system than to campaign and alter a component of the overall solution.

Lattice Work

I hope that this lattice-work of campaign approaches is clear and provides you with some ideas on how not to turn up late and influence the adoption of legislation.